50th anniversary of Depository of Dutch Publications

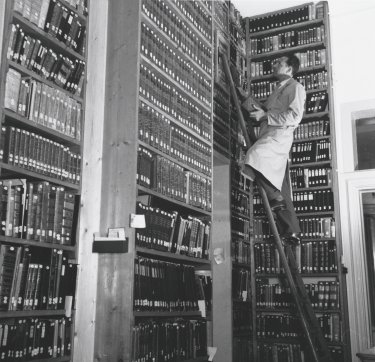

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Depository of Dutch Publications. This “depository” is where the National Library of the Netherlands (KB) stores all publications published in the Netherlands. The most important task of any National Library is to ensure that everything is preserved so that the past can be explored in the best possible way. The history of the Dutch depository is a remarkable story.

Preserving all of a country’s publications is the primary task of almost every National Library in the world. As the National Library of the Netherlands, the KB also has this task. The library term for this preservation function is: the national Depository. The year 2024 marks the 50th anniversary of the Depository of Dutch Publications. This joyous occasion is something to celebrate, because the national depository is an important foundation for Dutch culture and society.

The history of the Dutch depository is unique because it is relatively young and because, remarkably, the Netherlands has a “voluntary depository,” whereas almost all other countries have a depository act. Due to digitisation, in addition to the depository for paper books and periodicals, an e-depot has also been developed at the KB, for digital publications.

History of the Dutch depository

The Dutch depository is relatively young. Many other countries have had depository schemes in place for much longer. An example is the well-known dépôt légal in France, which has existed since 1537. Nevertheless, the KB has also had depository schemes as precursors to the current one.

1881-1912

In 1881, a new Copyright Act did give a strong impetus for a stricter form of deposit: copyright was linked to the submission of copies of publications. To be able to claim the rights as a publisher and protect against illegal copying, copies had to be submitted to the Ministry of Justice.

One of those copies was transferred to the KB. This meant that a substantial proportion of published books did find their way to the KB. These copyright copies can still be recognised in the KB collection by the publishers’ and printers’ declaration on the title page and the ministry’s stamps and numbering. Many of the editions of the famous Tachtigers (“Eightiers”) poets, such as Gorter’s May, were obtained by the KB this way.

1912

In 1912, the copyright act was replaced and copyright and copies were separated: starting in 1912, copyright arose upon the creation of the work. From 1912 onwards, publishers therefore no longer had to provide a copy to claim the rights. This also brought the mandatory depositing route to the KB to a standstill.

So the Netherlands no longer had a depository scheme from 1912. This had consequences, because the publications obtained by the KB from then on were selected and purchased by the specialists. And any selection has its limitations, as it may be guided by personal or time-specific views or opinions, for example regarding which books are considered ‘good’ and which are not. A depository scheme prohibits just that: it is non-selective and covers basically everything. The depository-less era lasted until 1974, and that resulted in a lack of many books in the KB's collection.

The study committee

Reedijk and his deputy librarian, historian Arie Willemsen, set to work on it. Some countries had had legal depositories for centuries, but by now the Netherlands had become a great exception worldwide as a country without a proper scheme. Willemsen later recounted how Dutch delegates at international library conferences were sometimes frowned upon because they represented a country “without a depository,” something that was baffling to many foreign librarians.

Willemsen and Reedijk lobbied the government hard, which in 1970 led to the establishment of a government Study Committee, headed by the KB, charged with paving the way for the “Legal Submission of Publications in the Netherlands.” The committee included representatives of the KB, other libraries, publishers and booksellers as well as officials from the ministries of Education, Culture, Recreation and Social Work and Justice.

The publishers and “the” Brinkman

The committee proceeded vigorously and the arguments provided for a depository act seemed irrefutable. At this time in the early 1970s, the KB was very optimistic about the chances of success for a Dutch dépôt légal, which would finally allow the Netherlands to “join the ranks of civilised nations in this respect too,” as Arie Willemsen put it in a retrospective.

This optimism was also fuelled by the excellent cooperation with the publishers of the Royal Dutch Publishers Association (KNUB). You might expect the publishers to have balked at any obligation imposed on them, but they (like all entrepreneurs) were instead very much in favour of clear rules from the government, rules that were the same for everyone.

And they also had an additional interest, because the publication of the time-honoured Brinkman's Cumulative Catalogue of Books fell into decline in the 1970s. That was a list of new books compiled by publishers to inform booksellers, started in the 19th century by Carel Leonard Brinkman. Until the 1970s, this was a commercial publication of Sijthoff publishers, but the publishers were keen for the KB to take over. This was quickly arranged within the study committee. Publishers would no longer send their new books to Sijthoff, but to the KB where they would serve as the basis for the new depository. And, at the same time, “the” Brinkman became the basis for the KB's National Bibliography.

Bibliographical centre

The KB and publishers worked together in unity. In anticipation of the new act, a bibliographic centre was established in the KB in the 1970s with a new KB department, soon to be called “Depository of Dutch Publications and Dutch Bibliography Department,” often unofficially referred to as “the Brinkman.” A new keyword system was set up to record national book production. That system of the strictly monitored Depository or Brinkman keywords is still in place.

In addition, an acquisition department was set up, because even with an act, the KB would still have to do considerable detective work. Even now, many think the KB acquires books “automatically,” but this actually still requires a lot of human work. Reedijk and Willemsen did carefully consider the nineteenth century and the faltering depository practice back then. The legislative proposal drafted in the study committee’s final report also provided for an article that would arrange that “KB officers” could be appointed as “sworn investigating officers.” This KB “detective” department could then itself claim books directly and impose fines if it did have to deal with unwilling publishers.

Retro

Policies for “retrospective collection” were also set up to identify gaps in collections from periods during which there was no depository. The study committee soon came to the conclusion that you could not oblige publishers to still provide publications from decades earlier, but that the KB had to develop its own policy for this by means of donations and purchases. This “retro policy” is still in place and has even been intensified in recent years in the context of current discussions on diversity and inclusion. The retro policy fixes the bias in the selections of the depository-less era.

The need for the depository

Later, Arie Willemsen sometimes regretted the practical decisiveness of the KB in the early 1970s, because the success of the voluntary depository prevented the establishment of the legal depository. But either way, the 50th anniversary is a joyous occasion, as the need for a national depository is undeniable.

The depository represents the norm that it is not the few or the elite of any kind who should decide which books should be preserved and which should not. The depository represents the principle that all books should be preserved. And the same applies to all newspapers and all journals and magazines. And the same will apply to all digital publications, for which the KB coordinates the e-depot.