Since 2013, nearly two million scans have been made of archival materials relating to slavery and the slave trade thanks to funding from Metamorfoze, driven by the subject’s historical and societal importance as well as current events. 2013 saw the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Suriname and the Antilles, and 2014 marked two centuries since the prohibition of the transatlantic slave trade.

As part of the projects, researchers poured over the sizeable archives of the West India Company (in the Dutch National Archives) and of the slave-trading company Middelburgse Commercie Compagnie (Zeeland Archives), both of which were placed on UNESCO's Memory of the World list in 2011. Even the archives left behind in Guyana (also designated as world heritage by UNESCO) were carefully shipped to the Netherlands for conservation and digitisation and have since been returned by ship to Georgetown.

In 2021, Minister Van Engelshoven presented the scans at a symposium on Sources on slavery and the slave trade, organised in collaboration with the Rijksmuseum and the Dutch National Archives. The final projects have now been completed, with follow-up projects set to be announced. The Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science has earmarked additional funding for the digitisation of even more archives and collections on the Dutch history of slavery, with a special focus on sources in the Caribbean. A call for project proposals was launched at the Metamorfoze symposium of 25 June 2024, during which several speakers also reflected on the projects relating to slavery and the slave trade. You can find a report of the symposium on Metamorfoze’s website or watch the entire livestream of the event.

Surprising sources have sometimes popped up from the newly digitised archives, with interesting bits on the Dutch history of slavery and plantations in the West Indies lying tucked away in the National Archives in London. The stories of how these sources got there are just as fascinating: hijacked, forwarded and meticulously recorded.

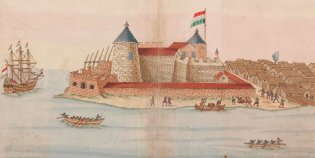

Hijacked: West African Fort Records, 1793-1803

The archival materials from Elmina, the headquarters of the Dutch on West Africa's Gold Coast, found in the so-called Prize Papers (High Court of Admiralty archive) in London were certainly a tantalising find. During the various wars between England and the Dutch Republic from the 17th to the 19th century, both sides frequently hijacked each other’s ships. The captured Dutch letters and shipping papers were kept in the Tower of London for centuries before being transferred to the British National Archives, where they were discovered by a Dutch researcher in the 1980s. The KB’s Sailing Letters project sparked great interest in the topic, giving rise to multiple follow-up projects in the Netherlands and beyond. The thousand or so boxes of Dutch material are a time capsule of sorts, as well as a treasure trove of archival material.

In 1803, 10 years of archives from the Dutch slave forts in West Africa were shipped to the Netherlands in the London slave ship Diamond, and while the English captain was a friend to the Dutch, his cargo never arrived in The Hague. The ship was hijacked by the French Bellona and subsequently recaptured by HMS Goliath, after which all the materials ended up in the UK’s National Archives instead of the Dutch National Archives.

The archives include records of 'general' correspondence from Elmina and field offices, along with muster rolls and pay books for personnel and soldiers, as well as records of all enslaved people working at the forts (including their names, origins, age and physical skills or infirmities: 'old and decrepit', 'blind in one eye', 'lame arm', 'sometimes mad', 'lumps under foot'). There are lists of merchandise and provisions, as well as detailed records of expenditures on goods and services (e.g. rowing to ships waiting off the coast). Various overviews and inventories were also kept, from available cannons and ammunition to medicines and instruments and lists of books and papers.

The archives cover a particularly interesting period: the final throes of the Dutch slave trade, marked by the rapid decline in the number of slave traders from Zeeland and Amsterdam. Fewer enslaved people were sold and the focus of slave buyers shifted from Angola to Elmina, which was quicker but not necessarily cheaper. The Dutch people at the forts also started selling more enslaved people to foreigners, including the English.

Some of the letters sent with the archive also turned out to include samples of beads and a pair of gold rings. Glass beads played an important role in the slave trade, while gold dust from the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) was sought-after return cargo. The highly colourful and undamaged beads are an exceptional find and the letters also provide new information about bead traders in the Netherlands.

The rediscovered archive from Elmina and the letters with beads were even mentioned in National Geographic Magazine and the magazine Tribale Kunst.

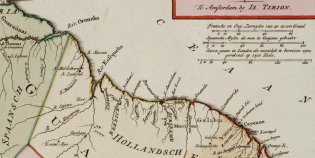

Forwarded: Essequibo, Demerara, Berbice, 1681-1795

But this is not the only unknown and unexpected material to have resurfaced. Tucked away in TNA’s Colonial Office (CO) archives are titbits of Holland’s and Zeeland’s history of slavery and plantations. The old colonies in the West Indies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries frequently changed hands between the Netherlands and Britain. For example, St Eustatius was briefly British in 1781, in 1801-1802 and from 1810-1816. Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice were British territory from 1796 to 1802 before being recaptured in 1803 and then formally ceded to Britain by the newly established Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1814. Suriname was British between 1799-1802 and 1804-1816.

There is a substantial amount of Dutch archival material about the so-called Wild Coast in modern-day Guyana, the former British colony that gained its independence in 1966. By its very nature, this material belongs in the National Archives in The Hague, much like the hijacked fort records. In the wake of the designation of the archives of the Dutch West India Company as UNESCO World Heritage, two parts of the Colonial Office archives have also been included in the Memory of the World register. First, a fine vellum-bound series of documents about Essequibo and Demerara from 1686-1792 (50 volumes, CO 116/18-67) sent to the Zeeland Chamber of the West India Company. The Zeeland chamber bore primary responsibility for these areas. Secondly, part of the archives of the Society of Berbice from 1681-1795 (69 volumes, CO 116/68-136), consisting of a series of administrative archives such as minutes and records, placards and notices, land deeds and mortgages, financial records, rulings of the Court of Justice and notarial records.

After Great Britain took over the administration of the Dutch colonies in 1814, they requested the transfer of the archives previously created in the area. It was mainly due to the procrastination and heel-dragging of the Zeelanders at the office of the former West India Company in Middelburg that only part of the WIC archives were sent to England, with the Minister of Foreign Affairs forced to intervene twice. As a gesture of goodwill, the West India Company would also add two beautiful maps but they were deemed of no importance as vastly superior maps were already available. The archives were finally transferred by royal decree in 1818. The Society Board in Amsterdam could not ignore a subsequent British request for records on Berbice, but while it responded promptly this time around, not everything was sent.

Meticulously Recorded: St Eustatius, 1781

The archives also contained revealing information about the populace of St Eustatius, including a record of the island's inhabitants after its conquest by Admiral George Bridges Rodney on 3 February 1781. St Eustatius had long been a haven for privateers and buccaneers – hence its nickname of the Golden Rock. It played an important role in supplying the rebels in North America, which did not sit well with the British. It took a large British force just two days to force the island to surrender.

In the years preceding the British conquest of the island, St Eustatius had played an important role in global politics. When the US warship Andrew Doria landed on St Eustatius for arms and ammunition on 16 November 1776, the Dutch governor Johannes de Graaff had her salute answered from Fort Oranje (the First Salute). To the rebels, it was seen as recognition of the American flag; to the British, it was betrayal by an ally. De Graaff was summoned to The Hague to account for his actions. Half-hearted apologies and unclear diplomatic support from The Hague and the ongoing smuggling trade led to the British declaration of war on 20 December 1780 and the subsequent capture of St Eustatius. This time round, De Graaff had to go to London as a prisoner of war to explain what had happened. The Republic declared war on England in May 1781. After France, the Republic was the second European power to recognise the independence of the United States of America (1782).

Following the island's capture, the British launched a census, as they were keen to find out who they'd find on St Eustatius. As an added bonus, Rodney had promised his crew a share of the spoils. The census is all the more interesting because the English destroyed the archives of the island administration in 1781, in stark contrast to their tendency to keep letters and ship papers captured at sea. Admittedly, these archives had already been decimated by a hurricane in 1772.

The Colonial Office archives still contain the result of Rodney's order to survey the island: 'An Alphabetical Liest of all Burghers resident in the Island of St Eustatius’. This Rodney Roll, as it was known, lists all inhabitants on the island by name, as well as their marital status, number of sons, number of daughters, male slaves, female slaves, boy slaves and girl slaves. As it turned out, St Eustatius had a surprisingly small population for an island of its commercial stature, with the census identifying 3,295 souls, including 1,631 enslaved people. The free population was made up of people hailing from the Netherlands and France, the US, Spain, Greece, Türkiye and even England and Scotland. Within a year, the French took over the area and Rodney's inventory disappeared into a drawer.

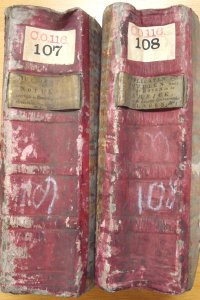

Meticulously Recorded: Suriname, 1811

When the English acquired Suriname in 1804, they proceeded in much the same way and carried out a new census. Thirteen leather-bound volumes contain the Suriname census, according to the proclamation of 17 October 1811 (CO 278/15-27). Together, they contain three series of bound 'returns', returned completed, signed and unsigned census forms (there are both pre-printed and written forms, in Dutch and English, showing the transitional situation). First came the records of enslaved people by plantation, with an alphabetical list of all plantations (over 500) with the name of the administrator and the number of enslaved people. Second is a numbered list of names of the white population, detailing all white residents, their families and their number of enslaved people. And third, a numbered list of the free black and coloured population, with their families and numbers of enslaved people. The names of the enslaved people were also noted, along with their occupations, tasks and other details.

In a letter dated 30 March 1812, Pinson Bonham, the interim governor of Suriname, meticulously listed the composition of the population by faith at that time, having inquired with the various church leaders (Reformed, Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Anglican, the German and Portuguese Jewish communities and the Moravian brotherhoods). Although they didn't keep records, they were still able to give an accurate account of the size of their congregations including the number of 'coloured people'.

According to Bonham, the totals were as follows:

- 'white inhabitants with their families: 2,029';

- 'their slaves of all descriptions: 7,115';

- 'the free coloured & black with their families: 3,075';

- 'their slaves: 2,599';

- 'total number of slaves of plantation or residence: 42,223';

- 'total number of souls: 57,041'.

The total number will have been somewhat higher still, as it did not include the Maroons, runaway enslaved people, or the original indigenous population, all of whom lived deep inland and not on the plantations. When Suriname returned to Dutch rule in 1816, the now unnecessary census was neatly stored in the archives of the Ministry of Colonies in London.

Hijacked, forwarded and meticulously recorded: extraordinary sources for the Dutch history of slavery and plantations in the West Indies, tucked away in an English archive. At TNA's request, a report of the Dutch sources was published in Magna, the official magazine of the Friends of TNA. The unexpected sources and their remarkable backstories paint a vivid picture of society in various colonies, providing a glimpse into the size of the free and unfree populations. This unused or little-used material on the Dutch plantation economy in the West Indies calls for further research. The scans have now been published on the website of the Dutch National Archives and more will follow thanks to the extra funding provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.